Servants. They are the shadowy shapes lingering at the edges of Austen’s scenes but rarely given more than the briefest of lines. The Longbourn housekeeper and manservant are perhaps the most active of any of Austen’s servants, having a major role in the last chapters when Lydia’s elopement is in its crisis. It is the opening scene of chapter 49: “TWO days after Mr. Bennet’s return, as Jane and Elizabeth were walking together in the shrubbery behind the house, they saw the housekeeper coming towards them, and concluding that she came to call them to their mother, went forward to meet her; but instead of the expected summons, when they approached her, she said to Miss Bennet, “I beg your pardon, madam, for interrupting you, but I was in hopes you might have got some good news from town, so I took the liberty of coming to ask.”

“What do you mean, Hill? We have heard nothing from town.”

“Dear madam,” cried Mrs. Hill, in great astonishment, “don’t you know there is an express come for master from Mr. Gardiner? He has been here this half hour, and master has had a letter.”

Away ran the girls, too eager to get in to have time for speech. They ran through the vestibule into the breakfast-room; from thence to the library;—their father was in neither; and they were on the point of seeking him upstairs with their mother, when they were met by the butler, who said,—

“If you are looking for my master, ma’am, he is walking towards the little copse.””

Secondary to that, we can credit the Dashwoods’s beloved manservant who creates a thread of tension and crisis by noting that he saw Mrs. Ferrars in town: “Their man-servant had been sent one morning to Exeter on business; and when, as he waited at table, he had satisfied the inquiries of his mistress as to the event of his errand, this was his voluntary communication,—

“I suppose you know, ma’am, that Mr. Ferrars is married.”

Marianne gave a violent start, fixed her eyes upon Elinor, saw her turning pale, and fell back in her chair in hysterics. Mrs. Dashwood, whose eyes, as she answered the servant’s inquiry, had intuitively taken the same direction, was shocked to perceive by Elinor’s countenance how much she really suffered, and a moment afterwards, alike distressed by Marianne’s situation, knew not on which child to bestow her principal attention.

The servant, who saw only that Miss Marianne was taken ill, had sense enough to call one of the maids, who, with Mrs. Dashwood’s assistance, supported her into the other room. By that time, Marianne was rather better, and her mother leaving her to the care of Margaret and the maid, returned to Elinor, who, though still much disordered, had so far recovered the use of her reason and voice as to be just beginning an inquiry of Thomas, as to the source of his intelligence. Mrs. Dashwood immediately took all that trouble on herself; and Elinor had the benefit of the information without the exertion of seeking it.

“Who told you that Mr. Ferrars was married, Thomas?”

“I see Mr. Ferrars myself, ma’am, this morning in Exeter, and his lady too, Miss Steele as was. They was stopping in a chaise at the door of the New London Inn, as I went there with a message from Sally at the Park to her brother, who is one of the post-boys. I happened to look up as I went by the chaise, and so I see directly it was the youngest Miss Steele; so I took off my hat, and she knew me and called to me, and inquired after you, ma’am, and the young ladies, especially Miss Marianne, and bid me I should give her compliments and Mr. Ferrars’s, their best compliments and service, and how sorry they was they had not time to come on and see you, but they was in a great hurry to go forwards, for they was going further down for a little while, but howsever, when they come back, they’d make sure to come and see you.”

“But did she tell you she was married, Thomas?”

“Yes, ma’am. She smiled, and said how she had changed her name since she was in these parts. She was always a very affable and free-spoken young lady, and very civil behaved. So, I made free to wish her joy.”

“Was Mr. Ferrars in the carriage with her?”

“Yes, ma’am, I just see him leaning back in it, but he did not look up;—he never was a gentleman much for talking.”

Elinor’s heart could easily account for his not putting himself forward; and Mrs. Dashwood probably found the same explanation.

“Was there no one else in the carriage?”

“No, ma’am, only they two.”

“Do you know where they came from?”

“They come straight from town, as Miss Lucy—Mrs. Ferrars told me.”

“And are they going farther westward?”

“Yes, ma’am—but not to bide long. They will soon be back again, and then they’d be sure and call here.”

Mrs. Dashwood now looked at her daughter; but Elinor knew better than to expect them. She recognised the whole of Lucy in the message, and was very confident that Edward would never come near them. She observed in a low voice, to her mother, that they were probably going down to Mr. Pratt’s, near Plymouth.

Thomas’s intelligence seemed over. Elinor looked as if she wished to hear more.

“Did you see them off, before you came away?”

“No, ma’am—the horses were just coming out, but I could not bide any longer; I was afraid of being late.”

“Did Mrs. Ferrars look well?”

“Yes, ma’am, she said how she was very well; and to my mind she was always a very handsome young lady—and she seemed vastly contented.”” (Austen, Chapter 47).

Many modern literary critics search for meaning related to Austen’s choices around how to portray servants. Below, you’ll find a list of articles related to the servant class from Persuasions On-line, an absolutely amazing repository of Austen-related academia.

“Droll Servants and Lasting Friendships”

“Privacy and Impertinence: Talking about Servants in Austen”

“I am a gentleman’s daughter.”

Ok, so that’s some modern takes on Austen and servants.

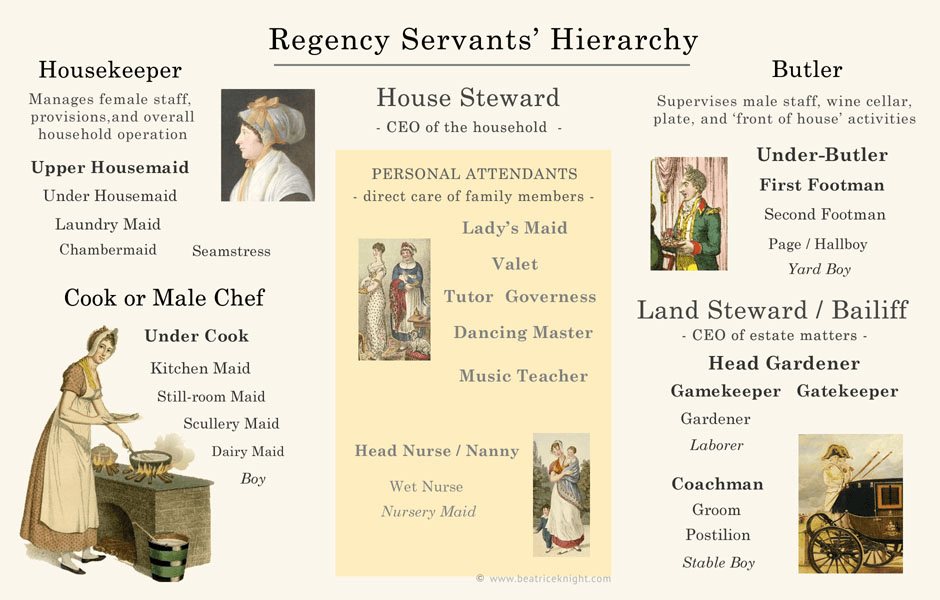

Now, let’s shift to some real nuts-and-bolts information about what it was like to be a servant. Ultimately, it comes down to balance: on the one hand, servants worked excessively long hours. A hallboy or scullery maid, the two lowest on the rung of servant class distinctions, might work nearly 24 hours a day with only a tiny amount of sleep. The housemaids would be required to wake before those they had to wait upon to help with breakfast and take up trays, then assist with dressing. They would continue to serve their “betters” until they went to sleep, their day spent responding to requests from upstairs, fetching for the butler, housekeeper, or cook, mending clothing, serving at meals, assisting with the clean up. On nights when the family attended a ball or engagement, their day could extend into the wee hours of the morning. Footmen largely served a similar role, being the front-facing attendants upstairs to answer the door, attend the master or mistress on outings, serve at meals, and care for all the “manly” items of the house.

On the flip side, servants were provided room and board and a half day off a week. Servants in better houses might even get a full day…ONCE A MONTH!! And you might think they got a good wage for all those hours of labor, but there were no such things as labor laws or protections (let alone retirement annuities or pensions, which would only have been granted by the most generous and wealthy of patrons. A lucky servant might be kept on in the house, as shown by Mrs. Musgrove, who kept on the family nurse, a woman who had raised all the children and was indispensable during Louisa’s medical crisis). So no, the wages were not good. They were enough to keep poor people from being destitute and desperate, but little else. Still, you can imagine people like Caroline Bingley or General Tilney imagining what a great service it is they’re doing by employing servants at a pittance and forcing them to work intense hours with little thanks or acknowledgement.

This was no easy lifestyle and yet, for those who came from large impoverished families, entering service might be the only thing between yourself and the workhouse or life as a criminal or prostitute. There just weren’t a lot of options. This also changed in the Edwardian period (the early 1900s for the most part), with a significant decline in service after WWI, when factory and city-based work largely replaced servitude, offering better wages and much more reasonable working hours.

Now, I’ve already talked your ear off, Dear Reader, and I’ve said that’s not what I intend this to be. So, in recognition of sticking it out with me, here’s a compiled list of additional sites and videos relevant to today’s exploration on Servants in the Regency Era.

“A Primer on Regency Era Servants”

“The Regency Town House: Servants”

The Jane Austen Center: Servants

“Being a Servant in the Regency Era was a Truly Terrible Job!”

Leave a comment